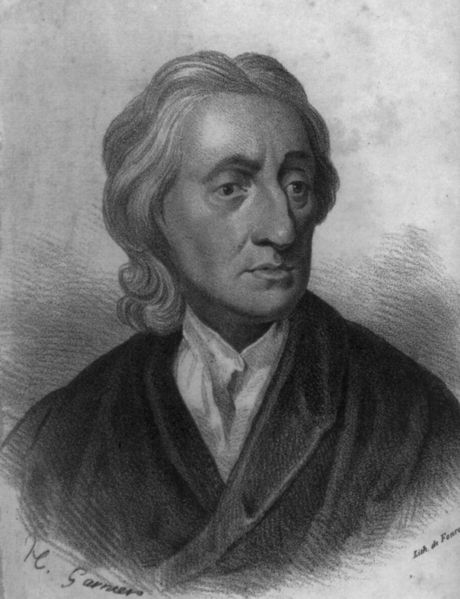

John Locke (b. 1632, d. 1704) was a British philosopher, Oxford academic and medical researcher, whose association with Anthony Ashley Cooper (later the First Earl of Shaftesbury) led him to become successively a government official charged with collecting information about trade and colonies, economic writer, opposition political activist, and finally a revolutionary whose cause ultimately triumphed in the Glorious Revolution of 1688. Much of Locke's work is characterized by opposition to authoritarianism. This opposition is both on the level of the individual person and on the level of institutions such as government and church. For the individual, Locke wants each of us to use reason to search after truth rather than simply accept the opinion of authorities or be subject to superstition. He wants us to proportion assent to propositions to the evidence for them. On the level of institutions it becomes important to distinguish the legitimate from the illegitimate functions of institutions and to make the corresponding distinction for the uses of force by these institutions. The positive side of Locke's anti-authoritarianism is that he believes that using reason to try to grasp the truth, and determining the legitimate functions of institutions will optimize human flourishing for the individual and society both in respect to its material and spiritual welfare. This in turn, amounts to following natural law and the fulfillment of the divine purpose for humanity.

(Source: http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/locke/)